LexisNexis Rule of Law Foundation has developed an extensive new tool to help track and compare the torrent of U.S. electoral law changes. In June 2022, a casually-dressed governor seated himself at a table, surrounded by aides and legislators, and picked up a pen to sign into law a bevy of new measures governing how future elections in one of the country's states will be run. Going forward, citizens won’t have to give a reason to request a mail ballot, nor will they have to find two witnesses or a notary to verify their signature. The state will set up a multilingual voter information hotline and update the list of registered voters at least four times a year.

In one form or another, this ceremony was repeated in all but two of the 50 states making up the United States in 2021 or 2022, as Democrats and Republicans sought to alter the laws surrounding who is entitled to vote in an election and – most crucially – how they can cast that vote. Some responded to the pandemic-era innovations in the presidential election of 2020 by codifying greater access to early voting or mail ballots; others imposed stricter identification requirements and sought to limit any potential for fraud. These measures in both red and blue states can differ widely, but they have in common their sponsors’ deep conviction that they are introducing changes that will strengthen the electoral system.

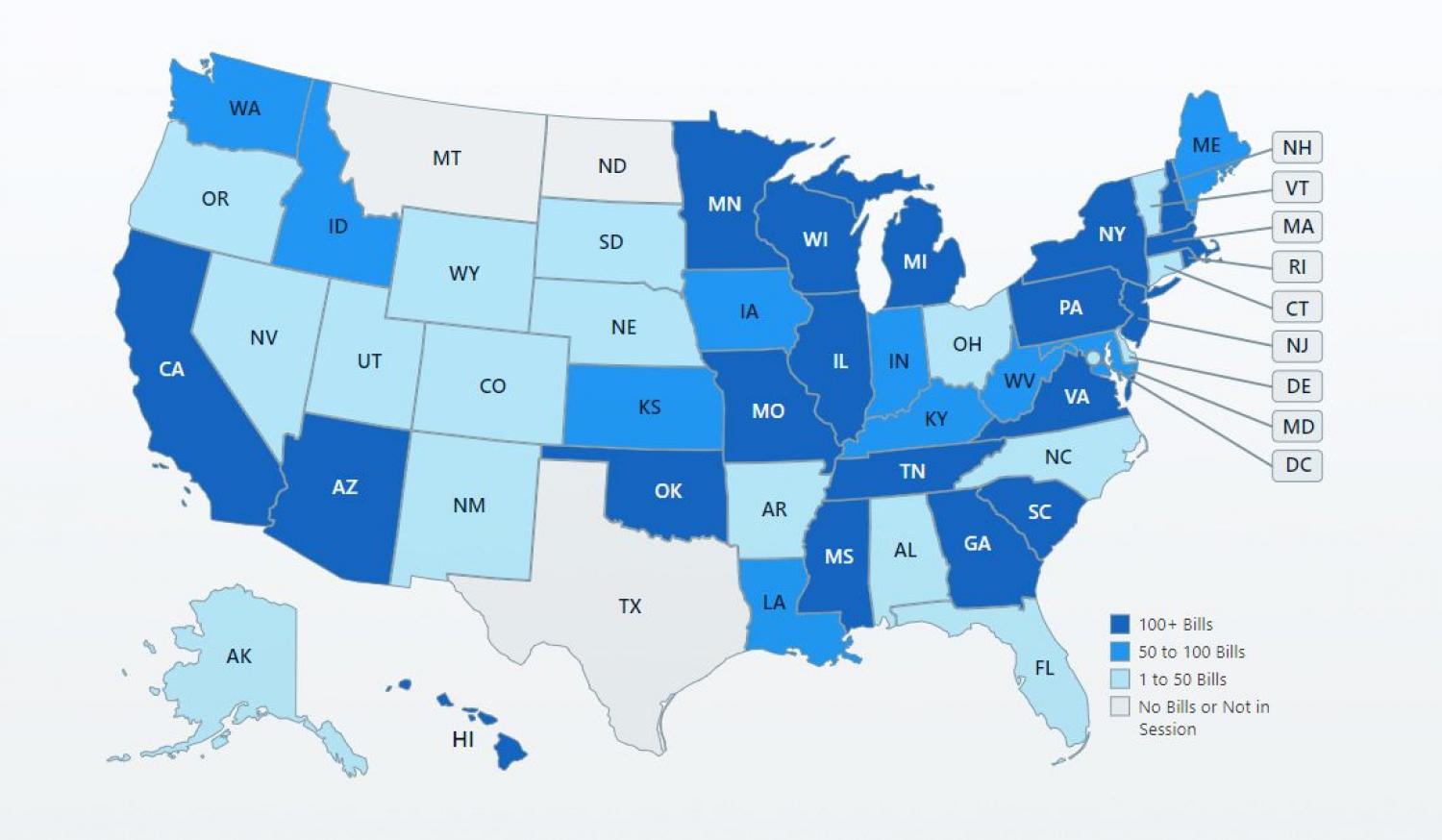

Almost every state has introduced or passed a sweeping array of new rules surrounding elections since the pandemic-era presidential race of 2020, and ahead of the 2022 midterms. Nationwide, a remarkable 487 new regulations have been codified this year alone and are in the process of being implemented. More are still pending, or were added to state electoral codes during 2021.

For election officials, ordinary citizens, lawmakers, lawyers, journalists, and civil rights groups, keeping up-to-speed with all these changes is an undoubted challenge. Simply tracking the status of proposed new rules governing elections – from the debate over each measure, proposed amendments and the final yea or nay ballots in state legislatures – can feel nightmarish.

Strengthening equality under the law

The LexisNexis Rule of Law Foundation has been working hard to help, creating an analytical tool that is now freely available to the general public, as well as to lawyers, legislators, scholars and students, nonprofit organizations, and electoral candidates and their parties.

“We wanted to shine a spotlight on U.S. voting laws to enable transparency for all,” says Mike Walsh, CEO of LexisNexis Legal & Professional, part of RELX. He proposed and has overseen the development of the new portal, the LexisNexis U.S. Voting Laws & Legislation Center. To advance the rule of law, he argues, means “strengthening equality under the law, transparency of law, independent judiciaries, and accessible legal remedy.”

That’s a more daunting task than ever before. When the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence, only white men with a certain amount of property had the right to a say in electing the fledgling nation’s first crop of legislators. It would take nearly two centuries and a series of constitutional amendments and new federal laws to ensure that all adult U.S. citizens over 18 – regardless of their gender, racial identity, religion and birthplace – possess and can exercise the right to vote. Native Americans – the continent’s original inhabitants – didn’t possess the right to vote until 1924 and the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, four years after the 19th Amendment extended the franchise to women. Many Black Americans possessed the right to vote only in theory until the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave them the ability to challenge attempts to undermine that right.

Today, the focus on ensuring and maintaining the right to vote, and in challenging any attempts to undermine that right, has shifted to less epochal but nonetheless important questions such as what ID voters need and whether they have the right to a mail ballot. “There’s an acceptance that the model is universal adult suffrage,” says Bill Barrett, an Indiana attorney and co-chair of the Uniform Law Commission’s committee studying electoral law. “The question of who gets to vote - felons, non-citizens, 16 year olds - has gone to things at the margin.”

Keeping up with the minutiae

These issues are still crucial to the health of American democracy, says Carlos Moore, president of the National Bar Association. “As a lawyer, as a judge, I believe very, very strongly in the need to maintain the principle of one person, one vote,” Moore says. “That’s why [at the National Bar Association] we have a non-partisan election protection task force. We will not allow any votes to be stolen, no matter how difficult that becomes.”

It is becoming harder, he adds, both because of the complex nature of some proposed changes, but also their volume. To monitor potential problems, to preserve access to the ballot of every qualified voter and to seek remedies under the law in response to any abuses requires keeping up-to-date on the minutiae of what are the election laws at any given time, in every jurisdiction in the country.

“The devil is in the details,” says Ian McDougall, president of the LexisNexis Rule of Law Foundation, and one of those who oversaw the development of the U.S. Voting Laws & Legislation Center. That’s true whether it comes to the ability of any citizen to know what’s changing that might affect how they can vote, or the challenges that the team at LexisNexis face now that the first iteration of the new tool has launched ahead of the 2022 midterm elections.

One of the biggest research challenges is the fact that laws affecting the conduct of an election can be found almost anywhere in the vast array of statutes and regulations, from a state’s constitution and its amendments, to the criminal code. A year after beginning work on the project, McDougall notes, “we’re still identifying relevant content and adding it to the site.”

The result is a massive database, which users can tap for information on what’s happening in a specific state or to seek out details of new and proposed laws that would affect key national questions, such as how and when early voting can take place.

So far, the online resource concentrates on what’s changing; down the road, Alison Manchester, vice president of primary law product management at LexisNexis says, the site’s scope may expand to include more historical data. For now, however, users can search some 20,000 existing federal and state voting laws and monitor the progress (or lack of progress) of amendments to these rules. Want to review Georgia’s much-discussed package of electoral law reforms? No problem: just head to the interactive heat map of the U.S. on the Voting Laws & Legislation Center’s website and click on Georgia; a window will pop up directing users to the complete text of the new rules.

Since legislators are debating new laws and proposing amendments at a rapid rate, the tool also updates what’s happening in nearly real time. To help users grasp the trends, LexisNexis researchers and developers have added a summary of news headlines related to electoral law on the landing page.

Users can search by theme or issue, as well as by keyword. Curious about what states are doing with respect to restoring voting rights to former prison inmates? Typing a request into the search bar will pull up a complete array of current rules and relevant case law. As Baby Boomers age, are states taking more steps to make voting more accessible, whether by mailing ballots to nursing homes or offering more assistive devices at polling locations? Which legislators are pushing the hardest for specific measures? And what’s the success rate of new initiatives, either in state houses or in the courts?

For all those involved in collecting and organizing the data, the task has often felt monumental, and it’s still not complete. Still, it wasn’t hard to keep the team motivated. “It was a passion project for all of us,” says Manchester, including the 50-odd staffers who volunteered time to work on the venture pro bono. After all, if knowledge is power then knowing precisely how elections – the essential ingredient of American democracy – are conducted ensures that power is distributed evenly, from a first-time voter to candidates for the highest offices in the nation. That, notes Manchester “is so central to our core values. We want, we need, an informed electorate.”